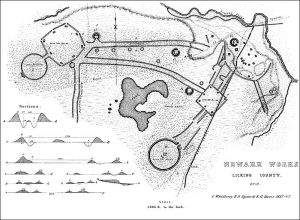

On Friday, October 2, 2017, ten students from the class “A History of Native America” took a field trip to Newark Earthworks “the largest set of geometric earthen enclosures in the world” and a site considered sacred by American Indians. Newark Earthworks is composed of three earthwork constructions that feature precise geometric shapes that once connected to each other. The landscape architecture bear testimony to the genius of the Hopewell culture, who constructed the sites between 100 BCE and 500 CE. What the earthworks’ builders called themselves is not known (archaeologists call them the Hopewell culture). Like the original name of the Hopewell culture, the purpose of one of the three sites—the Great Circle—is unknown. Based on oral histories and similar earthworks from other indigenous cultures, historians surmise that the Great Circle likely served a ceremonial purpose. We toured the Great Circle, which is close to 1,200 feet in diameter encircled by 12-foot-high, grass-covered earthen walls. Students both felt a strong sense of the relationship between indigenous people and the land and uncomfortable intruding upon a sacred space. Some appreciated the power of place and being able to experience the site; others pondered the ethics of visiting a sacred site. Each student came away with their own interpretation of the experience as the quotes below illustrate:

“Visiting the Newark Earthworks was a good experience that drove home several points that I learned in class but had never seen physically. The ties Native Americans have to the land, how the US government negatively impacted them, and the extent of the destruction of Native sites all seem much more real now than they did before.” —Claire Jennings

“Even though I learned an abundance of information, I still carry guilt for stepping directly upon ceremonial grounds.”—Sharah Hutson

“I appreciated that our tour guide was careful to assert historians’ uncertainties surrounding the ceremonial use for the Great Circle, and how he presented the unexplained site as an open discussion with limitless possibilities and interpretations. In doing so he drew parallels to other Nations earthworks and oral traditions, and common themes that run through Native narratives. While interesting, the attempt to answer the unknown by grouping and simplifying Indigenous oral traditions was precarious. I find it dangerous to simplify a group of people.”—Amy Wisseman